Semiquincentennial Fever

Discovering The History That Surrounds Us

I have an unrequited love/hate relationship with Ken Burns.

On one hand, I think he is a brilliant auteur who re-invented historical documentary filmmaking. First with 1981’s Brooklyn Bridge, and nine years later with his magnum opus The Civil War, Burns blended technique and narrative in a way that uniquely brought the distant past to life.

But with each film documenting the American experience, Burns’ over-reliance on his circle of experts increasingly reflected a myopic New England perspective and revisionist sensibility. I found this point of view becoming more and more prevalent over the decades and detracting from his later work – almost comically so in 2019’s Country Music.

That said, I have made a point to watch almost everything he has ever produced, waiting patiently for him to apply his technique to tell the story of America’s fight for independence. If any subject deserved the Ken Burns effect, it was our Revolutionary War.

Well, just in time for the Semiquincentennial, it arrived. Released in November, The American Revolution delivered everything I expected from Burns, both the good and the predictably annoying. He is still a master of his craft who unfortunately sacrifices appropriate emphasis (and sometimes facts) to serve his desired narrative.

But I’m not here to pick apart the 12-hour film. Others have already called out many of its problems – both large (no, the Iroquois Confederacy wasn’t a flourishing democracy that inspired the founding fathers) and small (no, Margaret Corbin’s pension was not half the rate that men received).

Rather, my biggest issue is that 12-hours wasn’t enough time!

In particular, the episode spanning the last three years of the war and its aftermath were covered at such a breakneck speed, it felt like I was watching the final season of Game of Thrones.

One of the glossed over aspects of the documentary was exactly how Washington’s army (joined by Rochambeau’s French force) marched some 450 miles from New York to Virginia for the war’s decisive Battle of Yorktown. The film mentions in passing how General Henry Clinton (Commander-in-chief of British forces in North America) was deceived to believe there would be an attack on New York, thus delaying any movement to re-enforce General Cornwallis’ position in Virginia.

With less than a minute spent on this ruse de guerre, I was intrigued enough to start doing some research of my own. I was delighted to learn that so much of this somewhat forgotten history led me to places very familiar to me.

The Chatham Deception: Washington’s “Ruse de Guerre”

Having lived in Chatham, New Jersey, I was aware that the town served as an encampment for the Continental Army and temporary headquarters for Washington on the way to Yorktown in the summer of 1781. There are two identical markers stating as such on Main Street. But I had no idea what a pivotal role the town actually played.

It turns out that Chatham was actually the focal point of one our country’s most successful military deceptions.

In order to convince Clinton that an attack on New York (via Staten Island) was imminent, Washington directed the massing of troops in and around Chatham and ordered the construction of French ovens and a 65-foot-long shed to house them. This new structure on the banks of the Passaic River could literally feed an army – and not just the Americans in Chatham, but the French troops encamped in Whippany just 6 miles away.1

The purpose of the project was to make it appear that the Americans and French forces were setting up a permanent encampment with some of the rearward capabilities needed to push the front eastward.

From his HQ at the Jacob Morrell House (now an Italian restaurant), Washington directed a misinformation campaign that had troops, residents and spies all believing the next move would be on New York. Only a select few in Washington’s circle knew the real plan.

After spending three days in Chatham, the French and American forces resumed their march south to Yorktown, leaving behind only a masking force in the village.

But it was enough time to change the course of history.

Believing that this troop movement south, not the Chatham encampment, was the stratagem, Clinton didn’t act. It wasn’t until Washington and Rochambeau were in Philadelphia that the British finally realized they had been outwitted.2

The Continental Army arrived in Yorktown with their French allies on September 28th and Cornwallis’ force surrendered 22 days later.

A Strategic Thoroughfare

It was not happenstance that Chatham was chosen as the setting of the deception. General Washington knew the village well from the Continental Army’s two long winter encampments at nearby Morristown in 1777 and again in 1779–80.

Situated within the Hobart Gap, a narrow passage through the Watchung Mountains, the road through Chatham (now Route 124/Main Street) became a vital thoroughfare. The road controlled the movement of people and supplies between Morristown and the British-held port of Elizabeth-Town (now Elizabeth).

The Watchung mountains helped keep rebel forces out of reach of the main British army while simultaneously allowing the Americans to monitor enemy activity in and around New York – only 20 miles away as the crow flies. Whenever British troops were perceived to advance towards Morristown, a formidable body of soldiers were dispatched to Chatham Bridge to guard its Passaic River crossing.3

In June 1780, a year before Yorktown, the big British push towards Morristown began. Sensing an opportunity to crush the depleted rebel army after the worst winter of the 18th Century, British and Hessian forces marched westward, culminating in the Battle of Connecticut Farms (now Union Township) and the Battle of Springfield, respectively. These engagements, the last major battles fought in the northern colonies, indirectly led George Washington to spend time in Chatham for a more charitable reason. (More on that later).

The Fighting Parson & The Murder of Hannah Ogden Caldwell

Reverend James Caldwell and his wife Hannah were stalwarts of the Revolutionary cause and pillars in the Elizabeth-town community. As pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, Caldwell served as Chaplain and Assistant Quartermaster General of the Continental Army. Forced to flee Elizabeth (their church and home were eventually burned down by Loyalists), Hannah and her children retreated further west to Connecticut Farms.

Unfortunately, this was a poorly chosen place of refuge as it was on that same road leading to Morristown.

As the alarms of attack sounded on June 7th, Ogden refused her husband’s request to retreat again. Determined not lose another home to arson, she stayed behind with her 9-month-old baby, her four-year old son, a nurse and another friend. Reverend Caldwell took the rest of their children with him to Springfield.

The New Jersey Brigade and militia held the British 1st Division at bay for a few hours until a second British division arrived and drove the Americans back towards Springfield. In the aftermath, British soldiers ransacked the town and set at least a dozen homes on fire. It was during this time that a British soldier fired his musket through a window of the Caldwell home, killing Hannah.

The exact circumstances were disputed. Hannah’s death was deemed an accident by Loyalists, but considered cold-blooded murder by Patriots. Regardless of the soldier’s intent, Hannah became an instant martyr for the cause of American independence and her killing played a critical role in galvanizing resistance against the crown.

The British fell back to New York after Connecticut Farms, but sixteen days later set out with a two-pronged attack with the objective of smashing through the Hobart Gap and taking out Washington’s forces for good.

The armies clashed at the Battle of Springfield on June 23rd and while the British succeeded in taking the town (and burning it to the ground), their advance was ultimately thwarted. It was during this fight that our newly-widowed Fighting Parson famously passed around stacks of his Watts’ Hymn books to provide ad hoc wadding so the American guns could keep firing.

Facing increased resistance, the British forces retreated back to Staten Island late that night. It would be their last military campaign into New Jersey.

The Caldwells in Chatham

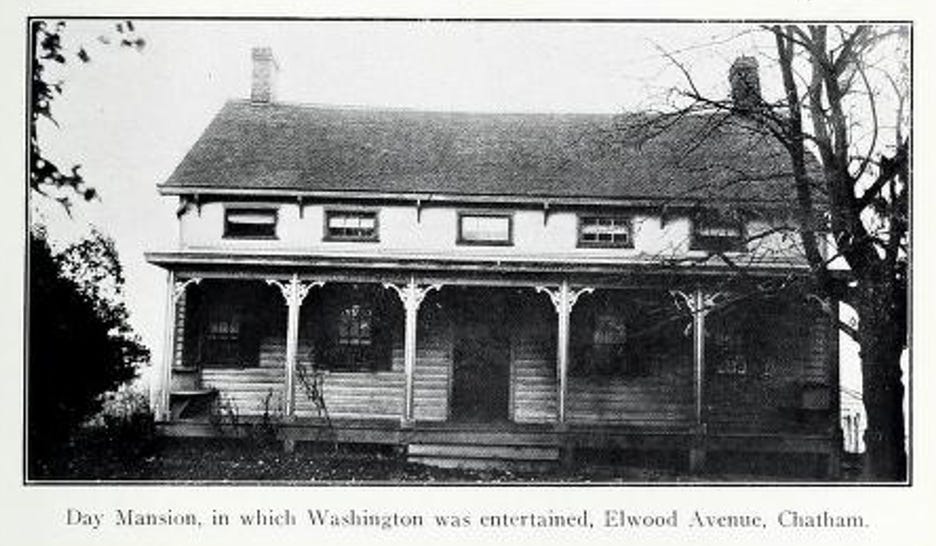

Hannah Ogden Caldwell’s sister Jemima Ogden Day was the wife of Stephen Day of Chatham. After Hannah’s tragic death, Reverend Caldwell – and all his children – moved in with the Days. Their house was located on the northwest corner of Main and Elmwood Avenue.4 People in the area today would know the property well – as it’s the location of the “new” Ogden Memorial Presbyterian Church, built in 1905.

While there is no marker on the property, nor mention of it in the Chatham Historical Society’s Self-Guided Walking Tour of Historic Main Street, according to A History of Morris County New Jersey:

After the battle of Springfield, General Washington on his return to Morristown sent word ahead to Mrs. Stephen Day that he would stop off to see her on his way through Chatham. Accordingly, Mrs. Day dressed herself in a fine black silk gown with a large white scarf about her neck and awaited the coming of her distinguished visitor. A small mahogany table was placed on the lawn in front of the house, and a pleasing repast was prepared for the General. The call was made and heartfelt words of sympathy were extended to Mrs. Day in behalf of the horrible murder of her sister at Connecticut Farms. Much appreciation was shown by the General for her hospitality and often afterwards it is said that Washington called at the Day Mansion.5

Unfortunately I was unable to confirm exactly where on the corner of Elmwood and Main the Day home was located, nor which direction it faced. But I suspect it was closer to the intersection than where the current Church sits.

I do think it’s worth knowing exactly where Washington was received on that front lawn. The only thing we can say for sure about the above photo is that it was definitely taken sometime between the invention of photography and 1905…

I hope that at some point the exact location can be determined and properly documented, if not formally landmarked, for posterity.

The Return of Lafayette

In further reading I came across another great tidbit that apparently happened just on the other side of that narrow Elmwood Avenue intersection.

Fast forward to 1824:

Visit From Lafayette6 — The year 1824 is a memorable one in the history of Chatham. Forty-one years had passed since the dreadful Revolutionary conflict had ended. It was at this time that a noted warrior of the Revolution now an aged man came to visit the scenes of warfare between Great Britain and her transatlantic colony. Again he passed over the road from Elizabeth Town to Chatham where his aide and distant relative, Count D’Anteroche, won the love of Polly Vanderpoel.

Elaborate preparations were made for the great general. The stars and stripes were flung from every home, and veterans of the war stood with uncovered heads when the revered Marquis D’Lafayette passed by. In the house where Mrs. Hamblin now lives, on the northeast corner of Main and Elmwood Ave, the Marquis was entertained. The main reception was held in Madison. A great number of the young girls of the town of Chatham, dressed in their prettiest costumes, took part in the formal exercises of the reception. No greater honor and heartfelt gratitude was ever given to any foreign visitor than that extended to the aged Lafayette.

This certainly explains why one of Chatham’s longest roads is named Lafayette Avenue!

The late Mrs. Hamblin’s house is no longer on the northeast corner of Elmwood and Main. It is now a small parking lot fronted with an even smaller public space. While there is another Chatham Historic District plaque commemorating the 1781 encampment, there is no mention of Lafayette’s visit to that spot in 1824.

There is, however, a marker in that tiny park commemorating something else.

Apparently some historic events are more important than others. Chatham does love its real estate!

The Semiquincentennial and You

As we celebrate the 250th Anniversary of our Republic, I think it’s a great opportunity to reflect on the history that took place in your own backyard.

George Washington may not have transversed your town, but no doubt someone or something of significance happened near you.

If you’re actually still reading this, I challenge you to go find it. You’re sure to go down some interesting rabbit holes on your journey.

I sure did.

Post Scripts

You can view the Chatham Historical Society’s Self-Guided Walking Tour of Historic Main Street here.

The most definite date concerning the early settlement of Chatham is 1730, when John and Daniel Day settled the area where the road crossed the Passaic river west of the Watchung Mountains. They came from Long Island, as did other early settlers.7

Chatham was named in honor of William Pitt. The Earl of Chatham was a supporter of American Colonist rights. Thankfully, the town was not named Pittsburgh.

Count D’Anteroche and Polly Vanderpoel did not live happily ever after. It is a really strange and sad story that is just too much of a tangent to fit in this rambling essay. But you can read about it in Ambrose E. Vanderpoel’s book referenced in the footnotes. (I think safe to assume Ambrose was related to Polly).

Calling it “The Hard Winter of 1779-1780” was an understatement. “New York Harbor froze over with ice so thick that British soldiers were able to march from Manhattan to Staten Island.” This was peak Little Ice Age. Saltwater inlets as far south as North Carolina were frozen solid.

During that winter, an exchange of prisoners was arranged for at the bridge in Chatham. General Winds was deputized to officiate for the continentals. After the transaction was completed the British field officer remarked on parting, “We are going to dine in Morristown some day.” “If you do,” said Winds, “you will sup in hell in the evening.”8

New Jersey’s Caldwell, North Caldwell and West Caldwell -collectively “The Caldwells” of Essex County - are named after Rev. James Caldwell.

From Philhower: The following incident shows how the Parson was regarded by the patriots of Chatham. Mr. Tuttle narrates that at one time when the Rev. Mr. Caldwell was about to preach in the open air in Chatham, an old soldier crowded to the front and cried out, before there was time to build a platform, “Let me have the honor of being his platform! Let him stand on my body! Nothing is too good for Parson Caldwell.”

More from Philhower: The soldiers wounded at Springfield were brought to Chatham and cared for in Timothy Day’s Tavern, which became a veritable hospital. Parson Caldwell and many heroic women joined in relieving the suffering soldiers housed within the town at this time. Day’s Tavern was located on the east side of Chatham Bridge.

The Fighting Parson did not live very long after moving his nine kids to Chatham. Rev. Caldwell was killed in November 1781 by a sentry in Elizabeth-Town when he refused to have a package inspected. The sentry was hanged for murder in Westfield, NJ amid rumors that he had been bribed to kill the chaplain.

The Official Seal of Union County, New Jersey (which seceded from Essex County in 1857) depicts the killing of Hannah Ogden Caldwell. In May of 2023, it was saved from being replaced after complaints raised by Mothers Against Domestic Violence pressured County officials to make a change.

I now know why The Sopranos was set in Union and Essex counties.

Ambrose E. Vanderpoel, History of Chatham, New Jersey (New York: Charles Francis Press, 1921), pgs. 368-383

Charles A. Philhower, A History of Morris County, New Jersey: Embracing Upwards of Two Centuries, 1710-1913, Volume I (New York and Chicago: Lewis Historical Publishing Co., 1914)

Vanderpoel, p. 55

Philhower, pgs. 283, 294

Philhower, p. 295

Philhower, p. 300

Philhower, p. 282

Philhower, p. 292

This is excellent, John. Crazy amount of research must have gone into this.

Since I grew up in the Midwest, most of my Indiana History skipped straight past the Revolutionary War, so a lot of our role in the country's early days was mostly claiming to have been The Boyhood Home of Lincoln. Alas, I'm sorta lost on everything that happened before the War of 1812.

It's also rather sad that a lot of this stuff isn't taught these days; a quick survey of my kids tells me that most all of what they picked up about the suburbs we've lived in — or the city of Chicago — was not taught in history class.

Again, a stellar article. Thanks for sharing!

Wow! This was so good! 😊

Maybe when you retire, you should work for a newspaper doing research & writing about it!

❤️🥰❤️